Autistic Artists and Plagiarism

I’ve been having a bit of an argument with someone on another site — a wiki — over his tendency to copy pages from other sites, instead of restating the information in his own words.

Stick around. This isn’t about SIWOTI. I promise I’ll get to the autistic artists soon enough.

I think we all recognize that there’s a difference between copying, and summarizing or paraphrasing. Paraphrasing is a two-step process: first, you read and understand the original text, that is, you convert it into an internal representation in your brain; and then you take that internal representation and turn it back into text. Copying, on the other hand, is a relatively mindless activity: you just take the original string of words and duplicate them.

Paraphrasing takes much more mental activity than copying, and that’s why it’s more respectable: if you can successfully paraphrase an article, that means you’ve managed to understand it, and have also managed to express thoughts in writing.

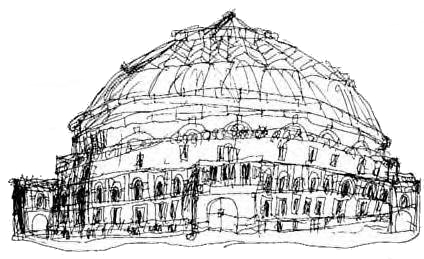

There are a number of autistic people with exceptional artistic talents: , Gilles Tréhin, Stephen Wiltshire, and others. Chuck Close isn’t autistic, but he is face-blind, meaning that he doesn’t see faces. Yet he’s an artist known for his portraits of faces.

|

What I notice about these artists is that their pictures are realistic. They seem to have an innate grasp of perspective. Windows and such are not evenly spaced on paper, but become progressivel closer as they are bunched together. Balconies and buttresses change orientation as they go around a building, and so forth. These are things that pre-Renaissance artists struggled with. (Okay, I’m not talking about Chuck Close so much here. More Wiltshire and Tréhin.)

And this brings us back to copying vs. paraphrasing.

The stereotypical child’s drawing has a house represented as an irregular pentagon, a tilted rectangle for a chimney, some curlicues for smoke coming out of the chimney, and one to four stick figures one and a half to two stories tall, standing on a flat expanse of green. In other words, it looks nothing like a house.

So I suspect that the way normal people draw is comparable to paraphrasing, as described above: when we see a house, or a tree, or a person, we don’t really see the lines, colors, and shapes formed on our retinas. All of that detail is processed, number-crunched, and turned into some internal data structure that represents the subject. For instance, I can instantly recognize my friends and family, even under different lighting conditions, or after the passage of time has altered their features. But I would have much more trouble describing them to you in such a way that you could pick them out of a lineup. I’d have even more trouble drawing a picture of them.

So when ordinary people draw a house or a face, we have trouble converting our abstract internal representation into concrete lines, because we never paid much attention to those lines. That’s one of the things you learn in art class. You have to unlearn the intuitive understanding of what a thing is, and look past it to see what the thing looks like. (This may be related to “first sight” in Terry Pratchett’s A Hat Full of Sky.)

But if someone has a problem recognizing things, if their world is a jumble of lines and colors, that may serve them in good stead in artistic endeavors, in that they’re not distracted by what things are, and can see what things look like. There’s an art class exercise in which you have to copy a picture — say, a portrait — that’s been turned upside-down. That way, the original picture is what it is, but it isn’t a face, and you’re not distracted by its being a face.

Just in case it wasn’t obvious, I’m not a neurologist, psychologist, or even an artist, so I’m not qualified to make pronouncements on this. But it seems like fairly nifty idea.