Cato Institute argues against NPVIC

The Cato Institute has an article arguing against the NPVIC. What I find interesting is that they use arguments that I haven’t seen a million times elsewhere:

Direct election of Electors: they argue that one reason the 1960 election was so close is that in Alabama, voters explicitly elected Electors, not presidential candidates. And that several of the chosen Electors were not pledged to any candidate. Under these circumstances, there’s no such thing as Alabama’s popular vote for president.

In this case, of course, the Secretary of State of each NPVIC state would, I presume, count the votes of people who voted for a pledged Elector as a vote for the candidate the Elector is pledged to vote for, and votes for unpledged Electors as “none of the above”: not votes for any presidential candidate in particular, so they don’t add to anyone’s tally.

Of course, while this sort of thing is both legal and in line with how I imagine the Founders imagined elections should be run, I can’t imagine any state adopting such a system any time in the foreseeable future: too many people are too used to the idea of voting for a presidential candidate to step away from that.

The Compact’s language simply assumes the existence of a traditional popular vote total in each state but it provides no details on how that is to be ascertained.

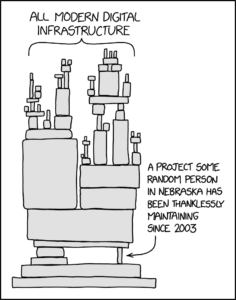

This is true. On one hand, yes, this seems like a flaw, since it provides little or no guidance in ambiguous or problematic cases. On the other hand, it gives a lot of power to states, the “laboratories of democracy”, which can come up with their own solutions.

Other shenanigans. North Dakota has already introduced a bill to publish a rough vote count, but withhold the precise vote totals until after the Compact states have to come up with a national vote winner. Yes, this is a clear jab at the NPVIC.Again, it seems the sensible approach for a Compact Secretary of State would be to take the minimum values of the rough counts and add those counts to each candidate’s totals.

In this particular case, North Dakota doesn’t have enough voters to make a difference in any but the tightest elections, but things could be different if a state like Texas or Florida tried to pull this. Of course, if Secretaries of State adopt the strategy I suggested above, that means that Texas or Florida would be reducing its vote counts (and its influence in the election) just to thumb its nose at a plan it doesn’t like. Which is not to say it couldn’t happen.

More generally, it seems likely that state legislatures will play silly games to try to undermine the NPVIC by blurring the vote count, making the Compact difficult to enforce, or otherwise. This could lead to some chaotic elections as states scramble to figure out how to come up with a popular vote when not all states are cooperating. In the long term, though, if the NPVIC passes, I suspect that people will quickly become enamored of directly voting for president, and won’t want to turn back the clock, not even to own the party they dislike.

Ranked Choice Voting. Maine apparently already used ranked-choice voting in presidential elections, and this does seem to present a special challenge.

I don’t think this is worth worrying about, though, since Maine already has to pick electors, which means they have to have a way of coming up with a final vote. I haven’t looked into this, but after some number of elimination rounds, some candidate gets N votes, where N is greater than 50%, and gets some number of Electoral Vote pledges. Maine also has a split system where not all of its Electors vote the same way, but however it’s decided, it has to boil down to “N votes > M votes”. So just add up the Ns to get Maine’s contribution to the national popular vote.

Cato’s objection, however, is a bit different: whoever wins the final round might actually end up with more votes than any of the first-choice candidates. So that creates an incentive for a candidate to not try too hard in Maine, and actually try to come out #3 or #4, rather than #1.

IMHO this seems fantastic. I seriously doubt that anyone can campaign with that kind of laser-precise skill. Candidates already have a hard enough time trying to be #1. I don’t know how you’d even manage to try to be #3 without seriously risking losing the election altogether.

But beyond that, ranked-choice voting is designed so that the candidates who come out ahead after several rounds are the compromise candidates that no one is especially excited about, but that everyone can live with. I would expect to see people like Bernie Sanders, Lyndon Larouche, Ralph Nader, Donald Trump — candidates that people feel very strongly about — to be at the top of ballots, and people like Joe Biden and Mitt Romney further down, under “I’ll settle for this person” rather than “I really want this person to be president.” So to the extent that Cato’s argument is true, it would seem that ranked-choice voting would tend to boost consensus or compromise candidates in Maine. And that’s fine.

Inconsistent results. The worst-case scenario envisioned by the Cato article is one in which different member states can’t agree on who won the popular vote, and allocate their Electors in an inconsistent manner. Once the dust settles, and the national popular vote is agreed on, it might be that the national popular vote winner didn’t get the presidency. I agree that that would be bad, but it also seems that the odds of this happening seem to be lower than one in nine, which means it’s already an improvement over the current system.