The Last Superstition: Software Is Immaterial

Chapter 4: Minds Are Not Material

In order to prove that human souls are immortal, Feser has to prove that there’s some part of a person that survives death, and the destruction of the body. If there’s a part of a human left behind when you remove the matter, that part must presumably be immaterial, and independent of the body (and in particular of the brain). Let’s watch how he does this:

Consider first that when we grasp the nature, essence, or form of a thing, it is necessarily one and the same form, nature, or essence that exists both in the thing and in the intellect. The form of triangularity that exists in our minds when we think about triangles is the same form that exists in actual triangles themselves; the form of “dogness” that exists in our minds when we think about dogs is the same form that exists in actual dogs; and so forth. If this weren’t the case, then we just wouldn’t really be thinking about triangles, dogs, and the like, since to think about these things requires grasping what they are, and what they are is determined by their essence or form. But now suppose that the intellect is a material thing – some part of the brain, or whatever. Then for the form to exist in the intellect is for the form to exist in a certain material thing. But for a form to exist in a material thing is just for that material thing to be the kind of thing the form is a form of; for example, for the form of “dogness” to exist in a certain parcel of matter is just for that parcel of matter to be a dog. And in that case, if your intellect was just the same thing as some part of your brain, it follows that that part of your brain would become a dog whenever you thought about dogs. “But that’s absurd!” you say. Of course it is; that’s the point. Assuming that the intellect is material leads to such absurdity; hence the intellect is not material. [p. 124]

Notice what he’s saying here: to make a triangle, you arrange matter in the shape of a triangle; to make a dog, you arrange atoms in a certain way, in the Form of a dog.

And, he tells us, in order to think about triangles, something in our cognitive process has to become like a triangle; to think about dogs, something has to become dog-like (including being dog-shaped). But since there’s no part of the brain (or, indeed, any other material part of the human body) that becomes triangular when we think of triangles, something else must be responsible for that aspect of cognition; something immaterial.

The most polite thing I can say here is “wow”. Clearly this is someone who doesn’t know the first thing about how software works, on the most basic level. I don’t expect Feser to be a programmer, but surely he realizes that the National Hurricane Center computers that simulate hurricanes don’t actually create rain and wind in the data center. That when you play World of Warcraft, there aren’t actually orcs running around somewhere.

(This reminds me of a post by Gil Dodgen at Uncommon Descent, about how a computer simulation of evolution would have to include random changes to the processor, OS, and so on. (My original response to that post here.))

Even if we granted Feser’s reasoning, above, it would only get him as far as “there’s more than just the brain; understanding the brain doesn’t mean that you understand the mind.” But he goes farther than that, telling us that “there is the fact that even though the intellect itself operates without any bodily organ” (p. 127).

If the soul can, unlike the form of a table, function apart from the matter it informs (as it does in thought), then it can also, and again unlike the form of a table, exist apart from the matter it informs, as a kind of incomplete substance. [p. 127]

Again, wow. This is like saying that since software is not hardware, it can run without any hardware. Or that since music comes down to vibrations, and since CDs don’t vibrate, that CDs aren’t involved in playing music. You wouldn’t expect to see tiny pictures if you look at a DVD through a microscope, or hear dialog if you listen to it closely enough, and yet this is the sort of mindset that Feser seems to be seriously considering, as far as I can tell.

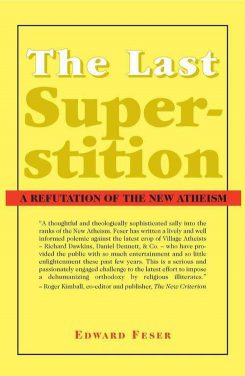

I can understand Aristotle and Aquinas making these sorts of mistakes: they lived at a time when people didn’t really distinguish between a book, and the words in the book. So it’s natural that, in groping around for these concepts, that they would make some mistakes. But Feser doesn’t have this excuse. Not only do we distinguish between book-as-words and book-as-object, we can put a price tag on this difference: as I speak, the hardback edition of The Last Superstition sells for $18.85 at Amazon, while the Kindle ebook costs $7.36 less.

There’s a bit in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy where two philosophers object to the use of a computer to figure out the Great Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. One of them says, “I mean what’s the use of our sitting up half the night arguing that there may or may not be a God if this machine only goes and gives us his bleeding phone number the next morning?” I feel we’re at that point with the “whatever it is that is the thing but isn’t matter”: Plato called it Form, Aristotle and Aquinas called it essence. We call it data, information, software, and we use it every day.

We understand software. Feser has no excuse for promulgating the sort of primitive thinking above.

Helpfully, Feser tells us why he doesn’t notice when his train of thought jumps the rails and plows across a field before getting stuck in a ditch:

Here, as elsewhere, the arguments we are considering are attempts at what I have been calling metaphysical demonstration, not probabilistic empirical theorizing. In each case, the premises are obviously true, the conclusion follows necessarily, and thus the conclusion is obviously true as well. That, at any rate, is what the arguments claim. If you’re going to refute them, then you need to show either that the premises are false or that the conclusion doesn’t really follow. […] The “findings of neuroscience” couldn’t refute these arguments any more than they could refute “2 + 2 = 4.” [pp. 125–126]

That is, Feser is so convinced that his premises are true, and that his reasoning is correct, that he doesn’t even bother with reality checks, though he does bring up science when it suits him:

When does the rational soul’s presence in the body begin? At conception. For a soul is just the form – the essence, nature, structure, organizational pattern – of a living thing, an organism. And the human organism, as we know from modern biology, begins at conception. [p. 128]

Not that he bothers citing any biologist to confirm this statement. Maybe this is one of those “obviously true” premises that he doesn’t feel the need to defend.

Far from any of this being undermined by modern science, it is confirmed by it. For the nature and structure of DNA is exactly the sort of thing we should expect to exist given an Aristotelian metaphysical conception of the world, and not at all what we would expect if materialism were true.

Oh, really? Then I’d love to see the book where Aquinas predicts the existence of a double-helix with “backbones” made of coal and phosphorus, scooping those atheist materialists, Francis Crick and James Watson, by centuries. Unless, of course, he’s just doing the same thing that every other apologist does: wait until scientists do the hard work of discovering something, then say, “Pfft! My god could’ve done that. In fact, he did, if you squint at this scripture just right.”

Naah, it’s definitely medieval prescience.

Modern Thomists still use this dog example:

https://disqus.com/home/discussion/strangenotions/why_sean_carroll8217s_the_big_picture_is_too_small/#comment-2791809877

(“Ye Olde Statistician” is a devout Thomist)

This seems so elementary in 2016

On the day that you share a comment about dogs, I see that Worm Quartet has posted a new song about dogs. Coincidence?

(Yes, coincidence. But fun.)

It doesn’t bother me that lots of Thomists use the same examples. After all, if “dogness” is a good, clear example of something that comes up a lot, why not reuse it?

Having said that, the dog example can be used, as you did, to show why “essence” or “form” isn’t a useful way of looking at the world. I think that makes it a good intuition pump.

Feser’s name showed up in my FB feed last week, with a link to his blog where he makes clear that *Descartes* is too new-fangled and modern for him. Then I spent a couple of hours Friday evening in the campus pub with an *atheist* who’s in love with Aristotelian Forms (and also the sound of his own voice, which is part of the problem….)

All of which is to say: it’s been a surreal past few days, philosophically speaking…..

Out of curiosity, was this atheist in the pub an alt-rightie? Just from cruising the blogosphere, it seems to me that there’s a fair amount of overlap between fans of Aristotle and/or Edward Feser, and the alt-right.

I don’t know whether that’s because both appeal to authoritarians who like order and structure, or whether I’m just seeing things, or what.

I’m not sure how much territory is covered by “alt-right”, but from brief previous interactions, I’d say he holds a mix of liberal and conservative views. He’s an American living here, and he loves Canadian healthcare. OTOH, he’s outrageously sexist based on simplistic ev-psych and thinks its good for the US to play Cop Of The World. Mostly though, he just thinks he’s Terribly Clever.

I concur on your “wow”. That has to be the most ludicrous argument I’ve ever read. It’s worth noting software is also matter so far as I know.